Reality Flows Top-Down but Modernity Fooled Us Into Thinking That It's Bottom-Up

Cleaning up the incoherent mess of "emergent" properties

The materialist understanding of the origins of life is that if you take enough non-living atoms, combine them somehow, then you’ll get a living being.

The same for consciousness: combine enough unconscious cells. . . and then *poof!* — consciousness emerges.

“Emergence” is not really an explanation for anything but rather a label atheists use that is functionally equivalent to brute juju magic. (Of course, the former label sounds more impressive and rigorous than the latter.)

The word “emergent” implicitly takes you on a mental journey where you might imagine individual parts hovering over a vacuum of nothingness, as they clump together, until somehow, something magical sparks from the clump.

When I watch this movie in my mind, I can’t help but to hear an accompaniment of sound effects along the lines of

vwubb vwubb vwubb vzzhhhhhh. . .

Polemics aside, let’s take the mystery head-on and point out what’s wrong with the emergentist’s parts-to-whole thinking—and really, how the Enlightenment itself has impaired our ability to understand the fundamental nature of reality.

Regardless of one’s philosophical viewpoints, the phenomenon we all need to account for is the fact that the whole can have properties that the individual parts do not (when considering a thing and the parts that make up a thing or many things combining to make a greater, whole thing).

Consider: Water is wet. But hydrogen and oxygen are not “wet”. You might be tempted to say that “wetness” is an emergent property of water. When you have the whole piece of H₂O, the “wetness” seemingly appears, even though the individual atoms don’t have it.

Similarly, but at a greater scale, you can consider the example of a dog. A dog has a certain nature that is typical for “dogness”. It sniffs out food, plays, looks for treats, chases balls, etc. It does what dogs do as opposed to what cats do. . . since it’s a dog.

But do any of the dog’s individual cells contain this property of “dogness”? Do the cells “know” that they are part of a dog, contributing towards the functions and ultimate ends of dogness?

Seemingly not.

So then, you might wonder, “Why can’t we just say the same thing about consciousness and life? None of the individual parts are alive or conscious, but when we see the whole, we see those properties of life and consciousness.”

Sure, we can say that, but again, we’re not really explaining anything by doing so. And in fact, the word “emerge” makes it sound like the flow of causality moves from the parts to the whole.

An explanation would involve answering what makes the parts unify to produce that property as opposed to some other property.

Or to answer questions like:

What makes the parts unify at all? And what unifies the parts so that they behave as one system rather than many independent objects? That the atoms unify into a single entity rather than a heap?

Why is a dog one thing and not 10¹³ independent particles temporarily cooperating?

From where exactly, and through what mechanism does a new substance emerge?

And what causes the transition at that moment instead of the moment before?

If mere quantity causes emergence, then adding more dead cells should increase life. But instead, it does the opposite: it increases rot.

Fundamentally, what makes a whole a whole, instead of just a heap?

By example, consider: What’s the difference between a pile of heart cells and an actual heart?

A heart is not just muscle tissue. A pile of muscle cells isn’t a heart.

So when we talk about the phenomenon of how parts become a whole, there are only three options:

There is a specific threshold where once you obtain the number of parts, the “whole” just happens.

There is no threshold.

There is a unifying principle of organization that’s already present.

The problem with 1) is that it’s completely arbitrary and unmotivated. Why this number of cells and not one fewer? If nothing about the nature of the parts changes except “more,” then the alleged threshold is just magic: “at N, poof.”

The problem with 2) is that if it were true, nothing could ever “become” anything. We would only see piles of parts, rather than any kind of new “thing”/ whole. If there is no real difference between “heap” and “whole,” then you never truly have a new thing—only different ways of grouping parts. But in experience, we clearly treat hearts, dogs, and persons as real unities, not arbitrary piles.

The correct answer is 3).

Why do the atoms form a cell? It’s not “because enough of them are stacked.”

It’s that the cell has a substantial form that makes them a unified living whole aimed at functions.

By “form” here, I don’t mean “shape,” but the organizing principle that makes a thing the kind of thing it is and directs it toward certain activities (its telos or built-in goals).

Why do the stones form a cathedral? It’s not “because they are near each other”.

It’s because they are arranged according to a form (plan, blueprint, telos).

The parts don’t self-assemble themselves; they always participate in a higher-order system that provides the organizing principle and gives identity to the parts.

A heart cell is a heart cell (as opposed to an eye cell) specifically because it contributes towards the function of the heart system (form) that it participates in. The part receives its identity from the whole, rather than the whole receiving its identity from the part.

Pause on that last statement for a second. . . and we’ll come back to it.

Let’s tackle the H₂O-water example again. Note the following crucial observation:

We cannot produce water by individually adding atoms together one by one.

You can’t just push an oxygen atom into two hydrogen atoms and then *poof* → water.

Instead we rely on pre-existing forms (systems) with chemical bonding dynamics that are already active; in a lab, we use conditions in which the higher-order bonding principles already exist.

When we “create water” we rely on fields, potentials, temperature, pressure, bonding laws—systems that already exceed the atoms themselves.

You would have to, for example, put hydrogen and oxygen gases at a 2:1 ratio within a single, pressurized container, heat it up to break the H-H and O-O bonds, and generate steam, which could later condense down to liquid water.

The point is that wetness does not “emerge” from stacking atoms like LEGO bricks.

It arises when atoms participate in a higher-order bonding form.

So when people say “wetness emerges from H₂O,” the crucial point is: it only does so when those atoms are already caught up in a system of fields, laws, and bonding structures that outrun any single atom. The so-called “emergent property” is really a top-down manifestation or inheritance of that higher-order form, not something being “pushed up” from the bottom parts.

Consider the following children in a bounce house analogy.

Imagine you have:

Two shy kids (hydrogen atoms)

One tall kid (oxygen atom)

You cannot force them to hold hands individually. But if you put them on a bouncy castle (high energy field), they bump together and naturally link arms because the environment gives them rules for interacting.

Thus:

In the same way that the higher-order bounce house conditions lead to the children holding hands, the higher-order chemical field is what determines the behavior of the atoms, rather than the atoms themselves.

Atoms do not create the laws that govern their unification.

They participate in a structure of order that precedes them.

This is true of any part. The parts participate in a structure of order (whole) that precedes them.

You can conceptualize this as a substance of a whole whose attributes or essence get distilled in some way down to the parts. The light of the moon is really a received light from the sun. The components receive their function from the broader system that gave rise to them.

Your intellect (part) is received from and participates in a greater source/field of intellect (whole). Yes, the parts still provide the mechanism for enabling the function of the whole, but it is the Form of the whole that unifies, organizes, and gives identity to the parts.

You can see how the concept of participation connects to knowledge of God in Step 7 of the following post:

So in many respects, we can assert that reality flows top-down—at least as far as meaning and intelligibility are concerned—as opposed to bottoms-up.

The principle of intelligible forms that both sets the definitional essence of what something is as well as organizes the participating parts into a coherent, goal-based system must necessarily pre-exist any aggregation process of those parts becoming a whole.

Some people will say, “That’s all I mean by ‘emergence’—higher-order patterns and structures.” Fair enough. My point is that, once you admit those real structures, you’re already smuggling in something like form and teleology. You haven’t explained them away; you’ve just renamed them.

I still dislike the word emergence because the metaphor runs in the wrong direction; it suggests something bubbling up out of the parts, like a creature rising from the water, when in reality the parts are receiving their role and identity from the prior order of the whole.

Now, why did I say that “Modernity fooled us” into thinking reality is bottoms-up, parts-to-whole? If you’ve been following my work for a while, you’ve probably heard me critique the Enlightenment on more than one occasion.

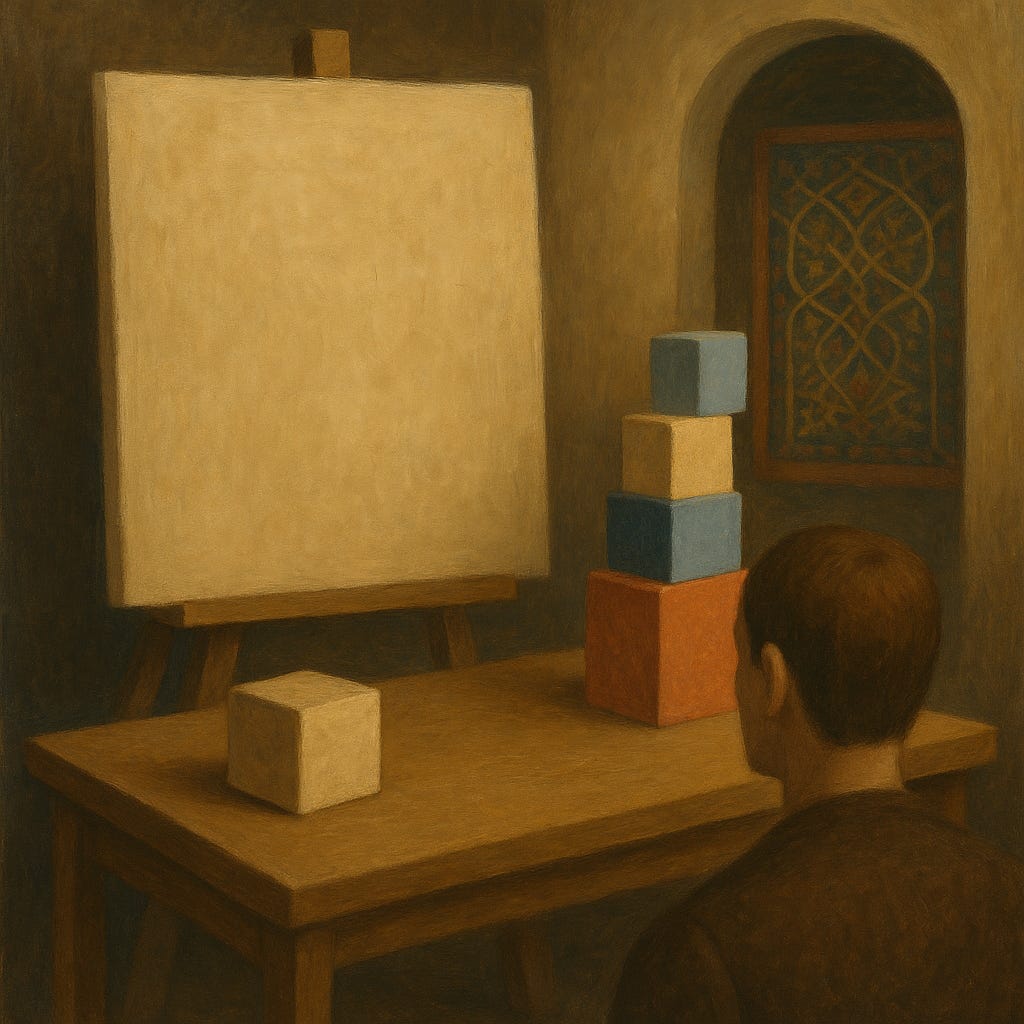

What I mean here is that we need to completely reevaluate the core notion of “blank slate” tabula rasa, where you force your mind to approach the world with a simulated imagined state of a blank canvas, and adding one piece at a time, building up your ideas, theories, and knowledge one conceptual block after the other, scrutinizing every individual block that would dare be brought forward to the examination table.

But of course, the issue is that the “examination table” or “canvas” that your blocks sit on is itself a thing with its own features. And it exists in a “room” with its own conditions. And the block that you put on the table didn’t come from nowhere; it was participating in a system (a whole) that you just ripped it from.

In other words, true isolation of being from other Being is impossible.

And most importantly: there is always a you who is the observer of this alleged “blank slate”. We should never forget that since you are a person with intellect and will, there is a WHOLE LOT that you bring to the table, and there is absolutely nothing “blank” about it.

So the idea of blank slate thinking is as ontologically realistic (despite its epistemic benefits) as thinking about a square circle.

Now, don’t get me wrong. . . the bottoms-up reconstruction process of “one part at a time, all else being equal” drives an excellent methodology that enables important empirical discoveries.

But it’s not everything. And it’s not even the most important thing.

We need metaphysical thinking to ground all of our parts into the ultimate coherent whole. It’s ultimately absurd to study parts without at least some conception of the intelligible whole that anchors them into being.

If I’m being fair, I’ll put it this way. . .parts-to-whole thinking has been tremendously beneficial for sharpening our epistemology while being atrocious in how it has disconnected us from ontology.

If you start with only parts and quantities, you’ll spend the rest of your life trying to explain away the very things that make life worth living—mind, meaning, purpose—as “emergent” quirks of the machine.

But if you start with intelligible wholes, forms, and participation, those same realities stop being embarrassing leftovers and become the main story.

Reality was never bottoms-up LEGO bricks. It was always, first and last, a tapestry of ordered wholes.

Yes. Which is the origin- the puddle or the cloud?

There is no heart without blood. There is no purpose to the heart if no blood.

So what is the motivator? Purpose. Volition. Act.

Life itself.

No one controls life. No one (should) control death.

But humans come to believe that we do or we can- and that is the Fall, described in the Christian Bible, a terrible delusion that produces the “flood “ of materialism.

Materialism is a scourge.

I believe this point of view is becoming more popular as reductionism refuses to answer the questions the people have where once upon a time it used to do the opposite. I explore pretty much this exact same issue in my first essay on this site but you did a fantastic job and hit points with such elegant simplicity that it really strengthens the argument. Great job.